The camera obscura is a device that uses a dark room or box with a small hole or lens to project an image from outside, upside down, onto the interior wall or screen. The term camera obscura was first used in 1604, but the phenomenon it describes has a long history. The earliest written record of the camera obscura theory is from the 5th century BC by the Chinese philosopher Mozi. The device was used for centuries to view eclipses without damaging the eyes and, from the 16th century, as an aid for drawing.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| First known written record | 5th century BC by Chinese philosopher Mo Ti (also known as Mozi) |

| First use of the term "camera obscura" | 1604 by German mathematician, astronomer, and astrologer Johannes Kepler |

| Use | Used as an aid for drawing and entertainment |

| How it works | Light enters through a small hole and projects an upside-down image of the outside world onto the wall opposite the hole |

| Name meaning | Latin for "dark chamber" |

What You'll Learn

The camera obscura's ancient origins

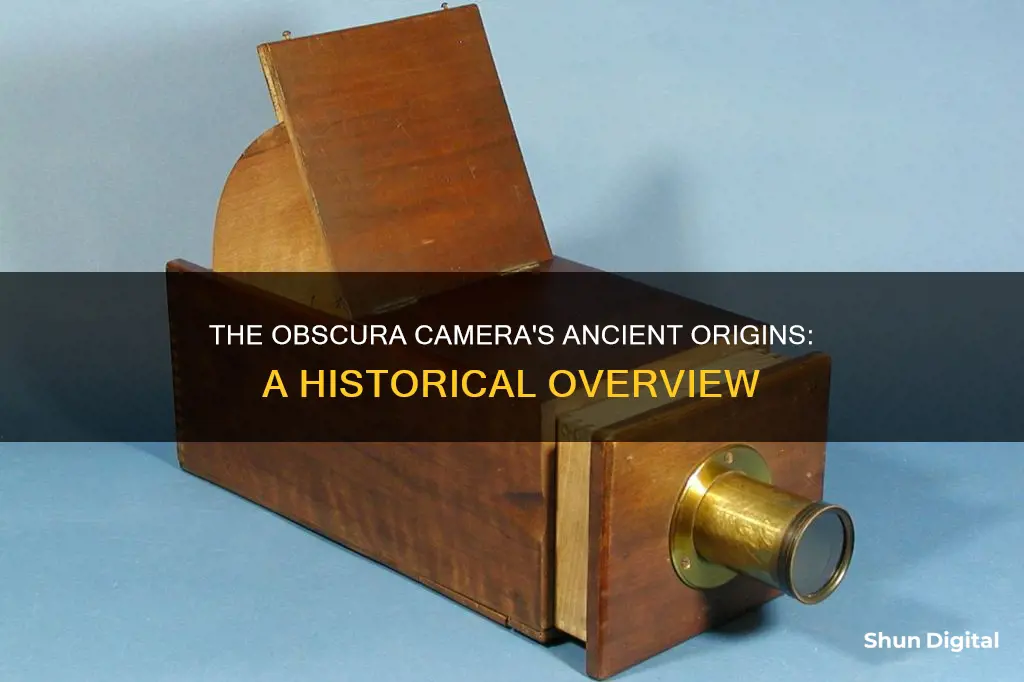

The camera obscura has a long and fascinating history, with origins that can be traced back to ancient times. The device, whose name translates to "dark chamber" or "dark room" from Latin, has evolved over the centuries, but the basic principle behind it remains the same: using light passing through a small hole to project an image.

The earliest known written record of the camera obscura can be attributed to the Chinese philosopher Mozi (also known as Mo Ti) in the 5th century BC. Mozi observed that light passing through a small hole into a dark room created an inverted image, as the rays of light travelled in straight lines. This phenomenon was also noticed and documented by Greek philosopher Aristotle in the 4th century BC, who observed the projection of a partial solar eclipse through the gaps in leaves and a sieve, allowing him to view it safely.

During the centuries that followed, several notable figures experimented with the concept of camera obscura. In the 6th century, Anthemius of Tralles, the co-architect of the Hagia Sophia, utilised a type of camera obscura in his experiments. Arab philosopher Al-Kindi in the 9th century, and Chinese scientist Shen Kuo in the 11th century, also experimented with the effects of light passing through a small hole.

It was not until the 11th century that a viewing screen was introduced to observe the inverted image, thanks to the work of Arab scientist Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham). Alhazen is often credited with the invention of the camera obscura, as well as the pinhole camera, which is based on a similar principle. He conducted experiments with candles and described how the image is formed by rays of light travelling in straight lines.

In the centuries that followed, the camera obscura continued to evolve, with Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci providing the first clear description of the device in his "Codex Atlanticus" in 1502. Da Vinci suggested that the human eye functions similarly to a camera obscura, and he drew around 270 diagrams of the optical device in his notebooks.

The term "camera obscura" was first used by German mathematician and astronomer Johannes Kepler in 1604. Kepler used the camera obscura for astronomical observations and even created a portable version that he carried with him.

The camera obscura played a significant role in the development of art and entertainment, with artists in the 17th and 18th centuries, such as Vermeer and Canaletto, using it as an aid for drawing and painting. The device allowed artists to trace the projected image, making it easier to achieve perfect perspective and detail in their works.

In the Victorian era, larger camera obscuras became popular attractions at seaside resorts, allowing groups of people to experience the phenomenon together. With the introduction of light-sensitive plates in the 19th century, the camera obscura also became the precursor to modern photography, marking its significance in the evolution of visual arts and science.

Understanding Camera Raw: Destructive or Not?

You may want to see also

The first written records

In the 4th century BCE, Greek philosopher Aristotle observed that a partial eclipse could be viewed by looking at the ground beneath a tree. The crescent shape of the partially eclipsed sun was projected onto the ground through the holes in a sieve and through the gaps between the leaves, allowing him to view it safely.

In the 6th century CE, the Byzantine-Greek mathematician and architect Anthemius of Tralles, co-architect of the Hagia Sophia, experimented with a type of camera obscura. Anthemius had a sophisticated understanding of the involved optics, as demonstrated by a light-ray diagram he constructed in 555 CE.

In the 9th century CE, the Arab philosopher, mathematician, physician, and musician Al-Kindi also experimented with light and a pinhole.

In the 11th century, Arab physicist Ibn al-Haytham (known in the West as Alhazen) extensively studied the camera obscura phenomenon. He carried out experiments with candles and described how the image is formed by rays of light travelling in straight lines.

In the 15th century, artists began to see the potential of using the camera obscura as a drawing aid. However, using the device sparked controversy, as many viewed the tracing method as cheating.

In the following century, Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) suggested that the human eye is like a camera obscura. He went on to publish the first clear description of the camera obscura in Codex Atlanticus (1502).

Charging the Disney Camera: Hannah Montana's Guide

You may want to see also

How it works

The camera obscura is an ancient optical device. In its simplest form, it is a dark room with a small hole in one wall. When it is bright outside, light enters through the hole and projects an upside-down image of the outside world onto the wall opposite the hole. The name camera obscura is Latin for "dark chamber". The image formed on the wall is inverted (upside down) and reversed (left to right).

The size of the hole has a significant effect on the projected picture. A small hole produces a sharp image that is dim, while a larger hole results in a brighter but less well-focused picture. This is because light travels in straight lines, a property known as the rectilinear propagation of light. As the pinhole is made smaller, the image gets sharper but dimmer. The optimum sharpness is attained with an aperture diameter approximately equal to the geometric mean of the wavelength of light and the distance to the screen.

Camera obscuras with a lens in the opening have been used since the second half of the 16th century and became popular as drawing aids. The addition of a lens increases the aperture size, resulting in a brighter picture but requires focusing. This can be achieved by moving the viewing surface or the lens. Things in the foreground focus further from the lens, while distant objects focus closer to it.

The camera obscura was widely used by astronomers for observing the sun without damaging their eyes. It was also used to study eclipses safely. In the 17th and 18th centuries, artists such as Vermeer and Canaletto used portable box-like versions of the camera obscura as an aid for drawing and painting. The introduction of a light-sensitive plate created photography.

Today, camera obscuras exist in two main forms: rooms where the viewer is inside the camera, looking directly at the image; and box types where the image is projected onto a screen viewed from outside. The screen is often made of ground glass and requires a cowl or hood to block out ambient light.

Charging Camera Batteries: Full Drain or Frequent Top-Ups?

You may want to see also

Its use in art

The camera obscura has been used in art since the 15th century, when artists began to see its potential as a drawing aid. The invention allowed artists to trace lines and shapes from a projected image, removing the need to meticulously measure out the lengths and angles of a subject or scene.

The first clear description of the camera obscura was published by Leonardo da Vinci in 1502. Da Vinci drew around 270 diagrams of the optical device in his sketchbooks. He also suggested that the human eye is like a camera obscura.

In the 16th century, the camera obscura was used by Gerolamo Cardano, who suggested using a glass disc to view "what takes place in the street when the sun shines". He advised using a very white sheet of paper as a projection screen so the colours wouldn't be dull.

In the 17th century, artists such as Johannes Vermeer and Canaletto used the camera obscura to project images that they then painted. Vermeer's "Officer and Laughing Girl" (1655-1660) is thought to have been created using the camera obscura, as the figure of the officer, who is sitting closer to the viewer, is much larger than the girl. The perspective is geometrically perfect, which was unusual in 17th-century paintings.

In the 18th century, the camera obscura was used by artists such as Paul Sandby and Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds' camera obscura, disguised as a book, is now in the Science Museum in London.

Yi Lite Action Camera: How Long Does the Battery Last?

You may want to see also

The development of photography

Ancient Origins

In its simplest form, a camera obscura is a dark room with a small hole in one wall. When sunlight enters through the hole, it projects an inverted image of the outside world onto the opposite wall. This phenomenon was observed and documented by ancient philosophers such as the Chinese philosopher Mozi (or Mo-tzu) in the 5th century BC and the Greek philosopher Aristotle in the 4th century BC. Aristotle, for instance, noticed that sunlight passing through gaps between leaves projects an image of a solar eclipse on the ground.

Medieval Developments

During the medieval period, several scientists and scholars experimented with the camera obscura and the properties of light. Notable figures include Anthemius of Tralles, a 6th-century Byzantine-Greek mathematician and co-architect of the Hagia Sophia, who used a type of camera obscura in his experiments. In the 9th century, Al-Kindi, an Arab philosopher and mathematician, also explored the behaviour of light passing through a pinhole.

Renaissance Innovations

The Renaissance period witnessed significant advancements in the understanding and application of the camera obscura. Leonardo da Vinci, the renowned Italian polymath, published the first clear description of the camera obscura in his "Codex Atlanticus" in 1502. He drew around 270 diagrams of the device in his notebooks, demonstrating his deep interest in optics. Da Vinci suggested that the human eye functions similarly to a camera obscura, and he also wrote about other inventions such as flying machines and musical instruments.

Portable Camera Obscura

In the late 16th century, camera obscuras with lenses became popular as drawing and painting aids. Artists and scientists continued to experiment with the device, and portable versions began to emerge. Italian scholar Giambattista della Porta improved the camera obscura by adding a lens near the pinhole, enhancing the image quality. This led to the creation of more compact and portable box-like versions that were widely used by artists in the 17th and 18th centuries, including masters such as Vermeer and Canaletto.

Transition to Photography

In the first half of the 19th century, the camera obscura underwent a significant transformation. The introduction of light-sensitive plates by J.-N. Niepce marked the birth of photography. The camera obscura, in its various forms, served as the foundation for the development of early photographic cameras. The magic lantern, introduced in 1659, also played a role in the evolution of projection devices.

In summary, the development of photography was a gradual process that built upon centuries of scientific inquiry and artistic experimentation. The camera obscura, with its ancient origins, served as a crucial bridge between the understanding of light and optics and the eventual creation of photographic images.

Charging Camera Battery Packs: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A camera obscura is a device in the shape of a box or a room that lets light through a small opening on one side and projects it on the other. The image outside the box is projected upside down. More complex cameras can use mirrors to project images right-side up and have lenses.

The earliest written record of the camera obscura theory was in the 5th century BC by the Chinese philosopher Mo Ti (also known as Mozi). In the 4th century BC, the Greek philosopher Aristotle noticed that light from a solar eclipse that passes through holes between leaves projects an image of an eclipsed sun on the ground. In the 11th century, a viewing screen was used for the first time to see the inverted image by Alhazen (or Ibn al-Haytham), who is said to have invented the camera obscura.

The camera obscura works by letting light through a small opening on one side and projecting it on the other. The image is projected upside down. More complex cameras may use mirrors and lenses to project images right-side up.